Restoring Electoral Harmony: Simultaneous Elections Can Strengthen Indian Democracy?

Implementation of the ONOE and the report of the High-Level Committee would bring to action a more efficient and democratic electoral process.

Total Views |

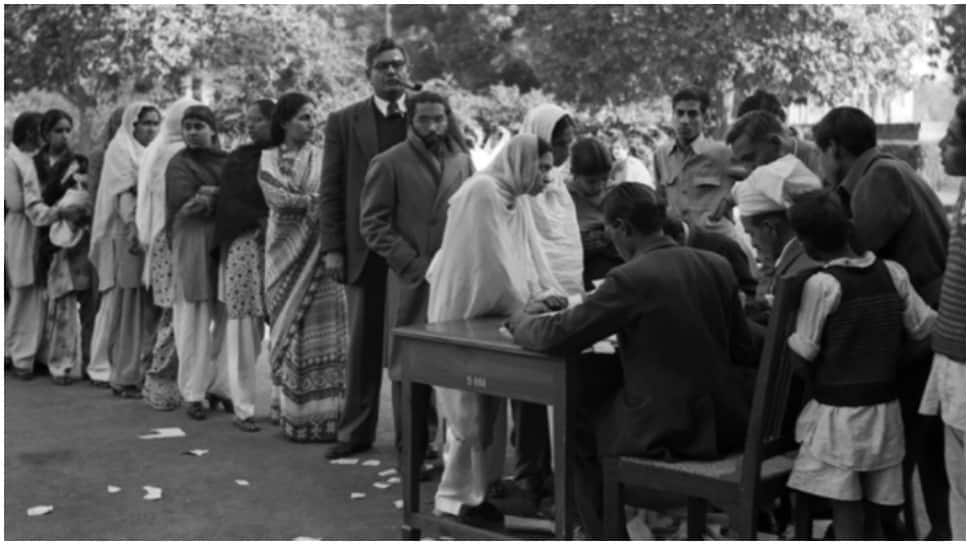

"The idea of simultaneous elections, often referred to as One Nation, One Election (“ONOE”)," is not a novel one within India's historical democratic structure, but it has its roots in our polity. The electoral history of India itself started with simultaneous elections, with the first general elections of 1951–52 enabling the citizens to vote simultaneously for the Lok Sabha and the state assemblies.

This electoral cycle remained unhindered through the 1957 general elections, where several state assemblies, including Bihar, Bombay, Madras, Mysore, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal, were dissolved to align with the national elections, ensuring the smooth functioning of a uniform electoral process, and now, in 2024, we see a blueprint of 18,000 pages detailing how One Nation, One Election can be brought about by 2029.

However, this synchronised system was overturned in the subsequent years. The first serious blow came in 1959 when PM Nehru dismissed the Kerala government led by E.M.S. Namboodiripad under Article 356 of the Constitution, which allows the central government to impose President's Rule in states under certain circumstances.

A second setback came when PM Indira Gandhi terminated the fourth Lok Sabha prematurely, necessitating a general election 15 months ahead of the schedule.

Those acts, combined with Article 356, which central governments led by the Congress party have utilised fairly liberally, meant an end for the simultaneous elections.

This provision, ostensibly provided to deal with exceptional circumstances, was activated at least half a century ago to unceremoniously dismiss state governments politically, not to the liking of the ruling party at the Centre, thereby essentially undermining the democratic balance and the election time.

Article 356 of the constitution, as a safety valve devised to maintain constitutional order in the states, transmogrified into an ill-will political tool and was exercised ad nauseum during the Congress regime.

This led to what many jurists describe as a dilution of federalism. Arbitrary dismissal of state governments led to the death of the simultaneous election cycle that has caused the electoral landscape to fragment, and simultaneous elections became an illusion.

It brought clear disadvantages with this fragmented approach. The Election Commission of India, in its 1962 General Elections report, observed the inefficiency of holding a separate election, noting that duplication of effort and expense should be avoided wherever possible.

The 1983 Annual Report of the Election Commission reiterated this, advocating for simultaneous elections to streamline the electoral process. In addition, the Law Commission's 170th Report was also very rigid in its conclusions and blamed the culprit for the loss of synchronisation that resulted due to the gross misutilization of Article 356, which recommended the reinstatement of simultaneous elections.

Key benefits of simultaneous elections are multifaceted. One most significant reason is that voters would only need to participate in elections once as far as the elections of the national representatives as well as state representatives are concerned. This would also greatly ease the logistic burden for the election bodies, as it would be needed only once after preparing and distributing polling personnel, security forces, polling stations, and electoral rolls.

Not to mention the craze of elections as we celebrate it like a festival in India. For instance, in 2024, the estimated spending is likely to total a whopping Rs 1.35 lakh crore, an amount more than double the amount spent in 2019, while over 3.4 lakh central security personnel deployed in the Lok Sabha poll alone.

Politically, ONOE would help level the playing field of the political parties by reducing the costs of campaigns. In addition, it will put an end to the frequent imposition of the Model Code of Conduct that does not permit the governments to announce new schemes or projects during the election processes.

The effects of administrative interruptions will be reduced in the sense that simultaneous elections ensure no iota of time is wasted in loss of governance. While for a long time, the report by ONOE had been perceived more as an ideological reform than practical in approach, the recent report by the High-Level Committee, approved by the Union Cabinet, has now emerged as a roadmap for its implementation in reality.

By a Panel of distinguished constitutional experts, with a former President of India Shri Ramnath Kovind and a former Leader of Opposition amongst them, which has presented several contingencies, such as the approach to be adopted in case of a hung assembly, thereby touching the concerns around the feasibility of ONOE.

Despite its merits, ONOE has attracted much criticism. Critics hold the view that it threatens the basic structure of the Constitution, particularly the principle of "free and fair elections."

The criticism relies on a series of judgements delivered by the Supreme Court that have reiterated the central place given to free and fair elections in the basic structure doctrine. On the other hand, proponents hold that ONOE would actually strengthen India's democratic fabric rather than compromise with it by streamlining the electoral process, reducing the expenses of elections, and providing for continuity in governance.

It is important to note that criticism of ONOE overlooks the fact that simultaneous elections were, once upon a time, a salient feature of the Indian democratic system and have been recommended by successive government panels even in the Congress regime.

The plea against democracy being weakened by ONOE is countered by the perception that, in actuality, it strengthens the process of elections and thereby makes them efficient as well as less politicised, particularly Article 356, which has, in the course of time, become an instrument of 'regime change' against the 'satraps'.

Implementation of the ONOE and the report of the High-Level Committee would bring to action a more efficient and democratic electoral process. Far from stymieing the constitutional basic structure, it may rejuvenate a harmonised system that was seen in India's democratic journey, which ensures not just federalism but also democratic governance intact.

Article by

Mohit Rawal

YoungInker

Law II Year, Campus Law Centre, Delhi University