Crushing Dissent: The Anti-Rightist Campaign in Communist China

The period known as the Anti-Rightist Campaign (1957-1959) serves as a powerful reminder of the dangers that come with unrestrained authority in Mao Zedong’s China. Following the Hundred Flowers Campaign (1956-1957), which had encouraged people to criticize the Communist Party, the Anti-Rightist Campaign emerged as a harsh crackdown on dissent.

The term “Rightist” was not consistently used with a strict ideological meaning during China’s Anti-Rightist Campaign. It functioned mostly as a political tag employed to stifle disagreement. Here’s a breakdown of the usual targets.

Intellectuals: Writers, academics, scientists, artists, and students formed a large part of those labeled “Rightists.” Their independent thinking and ability to express criticism made them perceived as possible threats.

Critics of the Communist Party: Anyone who voiced concerns about the Communist Party’s policies, leadership, or one-party rule risked being labeled a “Rightist.” This could include criticisms of economic collectivization, limitations on free speech, or Mao’s leadership style.

Those Deviating from the Party Line: People who held slightly divergent opinions from the official Communist Party position could also face persecution. The campaign sought to enforce strict ideological conformity, allowing little space for diverse perspectives.

Personal and Political Rivals: The campaign was also employed to resolve personal conflicts and eliminate political adversaries. Labelling someone as a “Rightist” was a convenient tactic to oust them from a position of power or influence.

Mao made a calculated decision that led to the Anti-Rightist Campaign. The primary goal of the Hundred Flowers Movement was to encourage constructive criticism, enabling the Party to address its weaknesses. Nevertheless, Mao became increasingly concerned about the growing dissent.

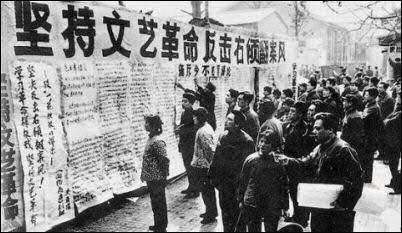

Intellectuals raised objections regarding the Party’s control over power, economic measures, and curbs on free speech. Mao suddenly changed his approach, labelling these critics as “Rightists” and enemies of the state, because of his fear of losing control.

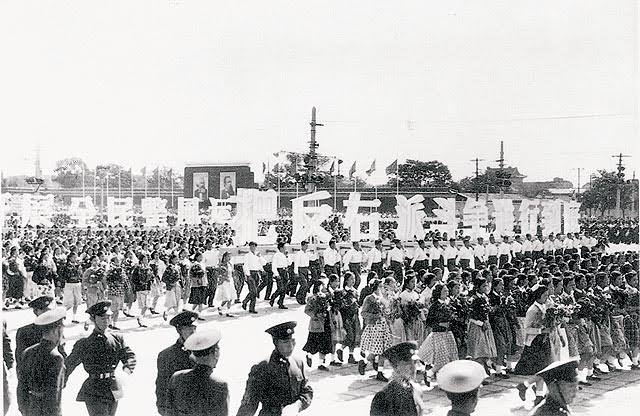

Universities, once known for fostering intellectual discourse, turned into arenas of conflict. A large number, possibly ranging from 550,000 to 2,000,000, were identified as “Rightists” and subjected to public shame, labor camps, and even death.

The consequences of the Anti-Rightist Campaign had far-reaching implications. China’s intellectual life was suppressed. The overwhelming fear caused people to censor themselves, resulting in a chilling effect on open conversations.

Additionally, the campaign had a negative impact on China’s economic growth. The group known as “Rightists” often comprised scientists, engineers, and educators who possessed valuable expertise crucial for the country’s modernization endeavors.

The Anti-Rightist Campaign also set the stage for the catastrophic Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. Mao’s consolidation of power and suppression of dissent allowed for the development of unrealistic policies and extreme ideological beliefs. Following Mao's death in 1976, many convictions from the Anti-Rightist Campaign were overturned during the Boluan Fanzheng period.

However, the psychological and social scars remained. Additionally, it took China several decades to recover from the vacuum created during this time of oppression.

Ultimately, the Anti-Rightist Campaign serves as a lesson to be learned. It exemplifies the hazards of manipulating political discourse and the devastating effects of silencing critical voices.

Despite the substantial economic and social transformations that China has undergone since the Mao era, the legacy of the Anti-Rightist Campaign stands as a poignant reminder of the significance of fostering open dialogue and being cautious of unrestrained power.

Article by

Pradeep Shrivastava

Author, Columnist

Software Consultant