Chinese Scholar Unveils China's ‘Three-Point Strategy’ To Takeover 2nd Thomas Shoal, Annex The Philippines

16 Aug 2024 09:05:30

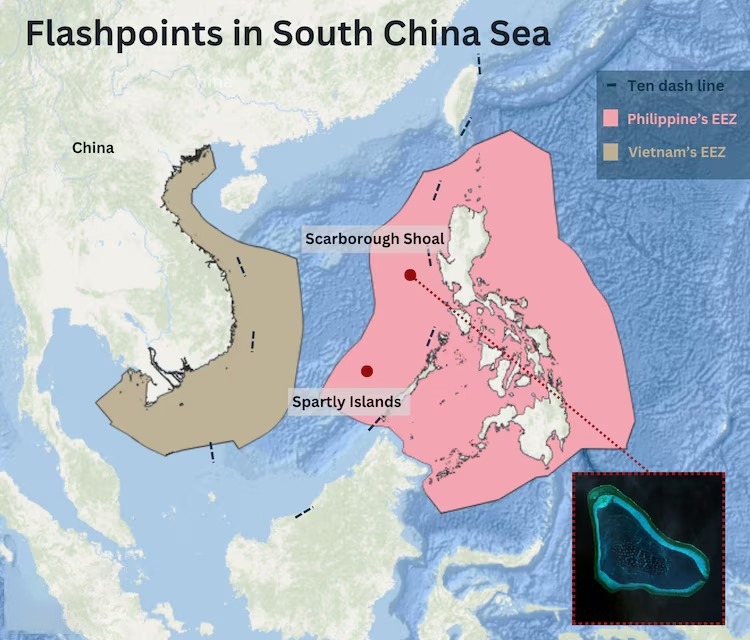

The tension in the South China Sea continues to grow with the ongoing conflict over Scarborough Shoal and Second Thomas Shoal. Both areas are within the Philippines' Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), which Beijing also claims.

Chinese academic Wu Shicun has outlined a provocative three-point plan to resolve the issue. The approach has, however, raised concerns among regional actors. Instead of calming tensions, Wu's approach would make the situation even worse in an already muddled geopolitical environment.

Scarborough & Second Thomas Shoals

Two of the major areas contributing to tensions between the Philippines and China are Scarborough Shoal and territory over parts or all of some Spratly Islands that both countries claim.

Scarborough Shoal: A group of rocks in the South China Sea, about 120 nautical miles (222 km) west of Luzon—the largest island in the Philippines—within its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). It is known as “Huangyan Dao” in China and Bajo de Masinloc (also Panatag Shoal) in the Philippines.

The Philippines has partial claims to the Spratly Islands, which number more than 100 islands and reefs. The islands are strategically important because of potential undersea oil and gas reserves and mineral deposits at sea north of the island areas.

Second Thomas Shoal: Another islet in the Spratly Islands that saw an incident earlier this week. It lies inside the 200-nautical-mile (370 km) exclusive economic zone of the Philippines but is also claimed by China. In the Philippines it is referred to as “Ayungin Shoal,” while China calls it Renai Reef.

The rocky outcrop is of strategic relevance and has economic value in the South China Sea. The waters near the shoal have been an epicentre for friction between Manila and Beijing regarding their territorial discord over the past year and a-half.

Chinese Aggression & The Escalating Dispute

The contentious issue of the shoals goes beyond just the primary claimants, extending to other regional powers and within a wider geopolitical context for dominance in seas with some of the world's busiest ports. China claims sovereignty over almost the entire South China Sea, which is also contested by the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia, and Vietnam.

By 2012, the Philippines and China were facing off with one another in their own tense standoff. The Philippines took its case against the Chinese takeover in Scarborough Shoal to the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

In 2016, the court ruled that China's claims on up to 90 percent of the South China Sea have no legal basis under international law. That ruling has not quelled tensions. South China Sea disputes between the Philippines and China have reached a tipping point, leading to an endless hostile exchange that includes trading accusations of activities destructive of local marine environments.

The BRP Sierra Madre Standoff

The BRP Sierra Madre is a crumbling Philippine navy ship that dates from World War II and sits at the centre of the long-running and increasingly bitter maritime standoffs.

This retired ship was transferred by the US to the Philippine Navy in 1976 and served a transport role until the early 1990s. Deliberately grounded on the Second Thomas Shoal 25 years ago (in 1999) to serve as a military outpost. Today it is staffed by only a handful of Filipino troops.

In the first week of July 2024, China demanded that the BRP Sierra Madre be removed as fast and as soon as possible due to its massive destruction to marine life. The South China Sea Ecological Centre's chief scientist, Xiong Xiaofei, said the vessel must be removed so that future destruction and lingering ecological damage to the Renai Reef coral ecosystem can stop.

The report said the permanence of Sierra Madre was causing “irremediable damage to the coral reef ecosystem” and that there would be no recovery unless it was taken out. That led to the rot of the ship's hull and discharge by Philippine soldiers manning it of human waste that posed "long-term hazards for coral heartiness."

Manila has, in near-repeat incidents since early 2023, faced problems resupplying forces aboard the vessel. Militarisation of outposts has occurred as China blocked Philippine resupply missions to the tiny outpost, causing showdowns between Chinese and Filipino vessels.

Beijing said it had a “gentleman's agreement” with former Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte, who pursued closer ties between the two countries while in power.

In a separate press release, Beijing said the Philippines can resupply the ship "out of humanitarian considerations" under that informal accord. Manila was obliged to give notice of resupply missions, allow Chinese on-site supervision, and precluded from transferring construction materials, the arrangement reportedly stated.

But his successor, Ferdinand Marcos Jr. (Bongbong Marcos), assumed office in 2022 and denied any such deal was ever made, leading to a deteriorating relationship between Beijing and Manila.

The latest and most severe confrontation occurred on June 17 when, according to Manila, a Chinese coast guard ship rammed into a Philippine resupply vessel, sinking it at the disputed Scarborough Shoal, in an encounter that left eight Filipino fishermen hurt, including one who lost his thumb.

Wu Shicun’s Three-Point Plan

Chinese academics are intensifying their efforts to assert Beijing’s claims in the contested South China Sea.

One of the South China Sea's leading scholars, Wu Shicun, founder of the Hainan-based National Institute for South China Sea Studies (NISCSS), stressed this point in a recent seminar: "Narrative construction and discourse building are absolutely important to ensure our rights and interests at all fronts, either today or tomorrow', as cited by the South China Morning Post.

Last week, as the drama escalated over Second Thomas Shoal, Wu Shicun suggested a radical 3-point plan to take hold of it. At the core of his plan is a suggestion to blockade the Philippines' World War II-era BRP Sierra Madre, which it grounded on the shoal as a symbol and assertion of its territorial claim.

Wu calls the continuing standoffs at the shoal a developing “bleeding wound” that needs to be treated before things get worse.

China’s measures to restore peace at the Second Thomas Shoal have come relatively late, and this situation may embolden the Philippines, Wu said in another interview with Chinese news outlet Guancha.

Wu, advocates China to "diplomatically set a timeline for the Philippines' withdrawal from the Second Thomas Shoal," specifying deadlines for military personnel and arrangements for humanitarian aid in the transition. Having a clear timetable, he says, might just end the cat-and-mouse game over the contested reef.

“In case of failure to abide by this proposed timeline, Wu argues that China needs to adopt a more hardline approach. He suggested that Beijing "prevent and block the Philippines from conducting provocative activities for changing the status quo," which means cutting off maritime and air-dropped resupplies to the reef.”

Such a blockade, according to Wu, could create a "survival crisis" for the Philippine troops stationed at the shoal. Therefore, China could, for humanitarian reasons, then establish a "special corridor" to allow the retrieval of the Philippine personnel from the 'temporary alert zone.'

This plan is nothing if not bold, and has sent out ripples across diplomatic circles from Manila to Washington. It's nothing short of a bold move in China's long-term strategy to take over the South China Sea, which each year witnesses the flow of trillions of dollars worth of commerce.

Will The Plan Resolve The Dispute?

According to The Geostrata, an Indian think tank, 'The plan assumes that this withdrawal will lead to the end of the cat-and-mouse game' between Manila and Beijing. Shicun's ideas mirror Beijing's aggressive strategy of imposing its dominance over the South China Sea. The so-called plans also presuppose there would be no action or reactions on the part of the other actors in the region.

But of course, the million-dollar question one would ask is whether Wu Shicun's plan will diffuse the territorial dispute or further escalate tension between China and the Philippines, or extra-regionally.

The answer, much like the shifting tides of the South China Sea, remains elusive. What is clear, however, is that this plan assumes other regional players will react passively—perhaps a dangerous miscalculation within the complex web of Asian geopolitics.

Article by

Shomen Chandra

Sub Editor, The Narrative