The Reality of Mao’s Rule and Mass Campaigns

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), under Mao Zedong’s leadership, often presents itself as the guardian of the people, the architect of a new, better society that overthrew feudalism and imperialism to create modern China.

However, this narrative glosses over the brutal methods used by Mao to consolidate power, the mass suffering under his regime, and the catastrophic social and economic policies that led to untold pain for millions of Chinese citizens.

Central to this authoritarian rule were the political campaigns—especially the Three-Anti and Five-Anti campaigns—intended to purify society of perceived threats to the CCP.

Mao Zedong: The Dictator

Mao Zedong’s rise to power in China did not result from democratic processes or a clear mandate from the people. His ascent was through violent revolution, leveraging the failures of the Nationalist government (the Kuomintang) to instill a regime based on ruthless control and ideological purity. Although the CCP initially appeared to be a movement for the people, it swiftly turned into a totalitarian dictatorship once Mao assumed full control.

Unlike the claims of benevolent leadership often made by CCP propagandists, Mao’s rule was brutal and authoritarian. There was no room for political opposition, and dissent was met with severe punishment. The nature of Mao’s dictatorship can be seen through the political purges, violent campaigns, and social upheaval that marked his tenure.

The Three-Anti and Five-Anti Campaigns: Political Purges and Mass Repression

The Three-Anti and Five-Anti campaigns are among the clearest examples of Mao’s totalitarian approach. Officially presented as efforts to cleanse Chinese society of corruption and capitalist influences, these campaigns were little more than tools for political consolidation and the elimination of anyone who might challenge Mao's authority.

The Three-Anti Campaign (1951-1952)

Launched in 1951, the Three-Anti Campaign’s primary focus was on government corruption, inefficiency, and the so-called "bourgeois" elements remaining within the ranks of the Chinese Communist Party. The campaign targeted Party members, government officials, and workers who were accused of bribery, wastefulness, and bureaucratic inefficiency.

It wasn’t just government officials who were affected by the Three-Anti Campaign—business owners, intellectuals, and anyone deemed suspicious of being "counter-revolutionary" were also targeted. The campaign quickly spiraled out of control as accusations flew, and paranoia took hold.

Those caught in the campaign were often sentenced to long prison terms, executed, or sent to labor camps for "re-education." The message was clear: dissent was not tolerated, and any perceived deviation from the Party line was grounds for severe punishment.

The Five-Anti Campaign (1952-1953)

Following the Three-Anti Campaign, the Five-Anti Campaign was launched in 1952 with the goal of targeting the private sector. It aimed to purge business owners, industrialists, and capitalists who were seen as a threat to the socialist agenda Mao sought to implement. The campaign focused on five main targets: bribery, tax evasion, fraud, theft of state secrets, and breaking contracts.

While these were legitimate concerns in any society, the Five-Anti Campaign went beyond reform and descended into a witch hunt against anyone with any semblance of wealth or power outside the control of the state. The capitalist class was singled out for attack, but it wasn’t just the wealthy who suffered.

In practice, the Five-Anti Campaign swept up anyone deemed to be a "class enemy," including those accused of harboring anti-Communist sympathies. The state used these accusations to justify widespread arrests, torture, and execution, and it created an atmosphere of fear that permeated every corner of Chinese society.

As with the Three-Anti Campaign, the Five-Anti Campaign was far less about combating real issues than it was about solidifying Mao’s control. Many business owners who had previously supported the CCP were turned into scapegoats, and a wave of paranoia and distrust spread through the population.

The specter of false accusations and arbitrary punishment kept citizens on edge, knowing that anyone, at any time, could be labeled a class enemy and subjected to brutal retribution.

Mao’s Authoritarian Rule: The Larger Picture of Oppression

Mao’s dictatorship was not limited to these two campaigns—it was a period marked by constant political purges, ideological conformity, and repression. The creation of a totalitarian state was achieved through the use of fear and violence, with the aim of silencing all potential threats to the Party’s control.

The Great Leap Forward (1958-1962)

One of Mao’s most infamous and destructive policies was the Great Leap Forward, a collectivization and industrialization program launched in 1958. Mao sought to rapidly transform China from an agrarian society into an industrialized socialist powerhouse.

However, the Great Leap Forward was built on flawed assumptions and unrealistic goals, leading to one of the most catastrophic famines in human history.

Mao's attempt to collectivize agriculture by forcing peasants into collective farms resulted in widespread starvation. The government’s exaggerated production targets for grain led to a false reporting of crop yields, and millions of tons of food were exported to other countries to maintain the appearance of success.

Meanwhile, the Chinese people were left to starve. Official estimates suggest that 15 to 45 million people died during the famine, though the true number remains unclear due to government suppression of data.

Mao’s refusal to acknowledge the failure of his policies and the continued support for the disaster is a clear indication of the kind of leader he was: one who would sacrifice millions for the sake of ideological purity and political expediency.

The Cultural Revolution (1966-1976)

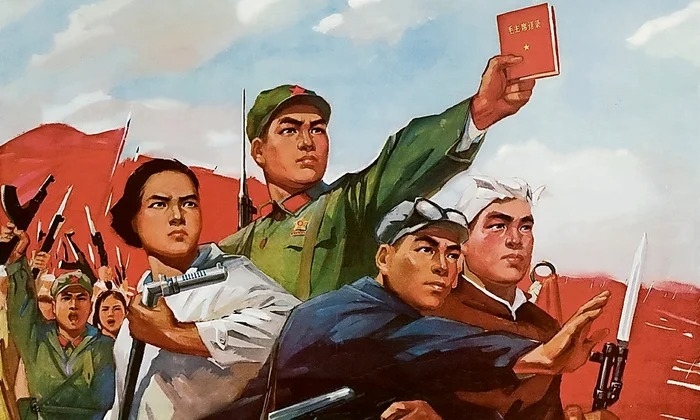

The Cultural Revolution, another of Mao's key campaigns, was intended to preserve Communist ideology by purging Chinese society of capitalist and traditional elements. However, it quickly devolved into a period of chaos, violence, and social destruction. Mao called on the youth of China to form the Red Guards, who were tasked with eliminating perceived enemies of the revolution.

The Cultural Revolution targeted intellectuals, teachers, artists, and anyone considered to be a threat to Mao’s vision. Cultural heritage sites were destroyed, and schools were closed as the education system was purged of "bourgeois" influences. The Red Guards engaged in widespread violence, publicly humiliating and torturing those deemed "counter-revolutionary."

As a result, millions of people were affected—either through direct persecution, forced labor, or brutal violence. The Cultural Revolution left an indelible scar on Chinese society, disrupting education, social stability, and economic development. It was a decade of madness, in which the ideals of the revolution were used to justify extreme violence and repression.

Mao’s Legacy: A Dictatorship That Never Truly Left

Despite the immense suffering caused by Mao’s policies, his image is still revered by many within the CCP. Even after his death in 1976, the Chinese Communist Party maintained a tight grip on power, and Mao’s ideas continued to influence the direction of Chinese society. However, the more pragmatic leadership of figures like Deng Xiaoping after Mao’s death has allowed China to gradually open up economically, while maintaining strict political control.

The Chinese Communist Party, despite claims of progress and modernization, continues to be an authoritarian regime. It may have evolved since Mao’s time, but the methods of control, surveillance, and censorship remain central to its governance. The CCP’s use of Mao’s image as a symbol of legitimacy is a reminder of the deep roots of authoritarianism in the Party, and the legacy of violence and repression that continues to shape China today.